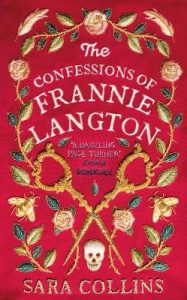

It has been a long time since I have had the time to review a book on this site, so please pardon my extended hiatus. I listened to the audio book version of Sara Collin’s The Confessions of Frannie Langton last week and have not been able to stop thinking about it since. If you are interested in historical fiction with a gothic Frankenstein-esque twist which highlights women’s experiences and does not shy away from the worst of man’s predilection for inhumanity, I highly recommend this book.

It has been a long time since I have had the time to review a book on this site, so please pardon my extended hiatus. I listened to the audio book version of Sara Collin’s The Confessions of Frannie Langton last week and have not been able to stop thinking about it since. If you are interested in historical fiction with a gothic Frankenstein-esque twist which highlights women’s experiences and does not shy away from the worst of man’s predilection for inhumanity, I highly recommend this book.

It is the late 1800s and Frannie Langton, a formerly enslaved Jamaican woman, is on trial for her life in a London court.She is accused of murdering her employers, renowned scientist Benham and his alluring French wife, Marguerite. Frannie does not recall the hours before the murder, before she is found in a deep sleep next to Marguerite’s dead body, and so she is not 100% sure of her own innocence in this matter. As Frannie’s story, filled with layer after layer of intrigue, unfolds in a tell-all letter to her lawyer, revelations are unveiled which reveal a depravity, a rotting in English society.

Frannie is born on a plantation in Jamaica called Paradise. She is brought to London by her master, a scientist by the name of Langton, and handed over to another scientist Benham as payment for a debt. While Frannie is technically free, she finds herself still enslaved, in part because she is not being paid by her new employer and in part because of her inability to move from where she is placed. Frannie is extremely well-read and careful readers will find many links between the books mentioned in the text and the circumstances of Frannie’s life. Collins draws the England of Dicken’s time with painstaking and hauntingly beautiful detail–dark, damp, and dangerous with rain never powerful enough to cleanse man’s wickedness.

The reader does not discover the sad truth of the double-murder until the very end of the story. I did not guess how it would turn out, which is highly unusual and a testimony to the gripping nature of the story. I was much too engrossed in Frannie’s recounting to look out for hidden clues or suspects.

This is a story, in part, about the impact of guilt and trauma, emotions Frannie knows intimately from a tender age. We discover that, even if she is innocent of the murders for which she is on trial, she has committed horrific acts for which she believes she should be punished. Should this confession to her lawyer save her from being hanged? I would never have had the opportunity to have been on her jury, it was all male, after all, but I find myself wondering how I would have reconciled holding her responsible for her crimes when she had been led, bred even, to believe herself incapable of choice, incapable of being her “own woman?” And can we really blame her for attempting to reign in the hell into which she has been unfairly cast? From start to bitter end, the book is filled with all the irony that must be a part of any tale involving such gross injustice.

The book also plumbs how close to hell man will willingly descend to protect his way of life and his belief system. Additionally, it explores whether people of different classes can have a relationship based on anything besides servitude and indebtedness.

There were a few places where I felt frustrated with the pacing of the story, particularly in the development of the relationship between Frannie and Marguerite and all of the damage that this causes to Frannie. While the author appears eager to peel back horrific layers of her male characters, she appears equally eager to spare her female characters, providing them with sympathetic backstories not afforded her rich male characters. There is irony in the fact that the two former enslaved people we get to know best are of high intellect and wit, ironic because one of the puzzles the British scientists in the story set out to solve is to prove the inferior intellect of the black race, especially after being forced to concede that black and white people are of the same species. In this way and others, the characters appear to represent clear lines between black and white, good and evil, underpriveleged and rich, that on close examination may seem too cut and dried.

Those were very minor notes I made searching for something to critique in a powerful and gripping novel. Overall, I found it a wonderful read, and while I am not sufficiently familiar with 1850 Britain, the attitudes of British plantation owners, or the science of that time to assess the historical accuracy of the book, it reads true, too God-awfully true.