|

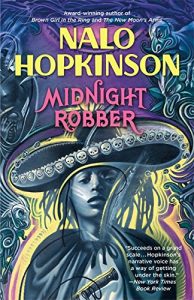

Sometimes when I stay up reading until 3 am, it’s because I can’t sleep, and sometimes it’s because a book is so captivating I cannot stand to go to sleep until I know what happens to the protagonist. Midnight Robber by Nalo Hopkinson fell in the latter category. I needed to know the Tan Tan’s fate before I could sleep soundly. This is not a new book, it was first published in 2000, however, it is now April 2020 and so I have a little extra time on my hands. |

(This synopsis is intentionally vague to avoid spoilers.) When we enter Tan Tan’s world, we find her a young child living a life of great privilege. She has staff at her beck and call including an Amazon-Alexa type device in her ear which she can call upon to answer questions, to give her history lessons, or to provide entertainment. Manual labor is considered blase in this world, “the old-time way.” This modern society on Touissaint operates via a highly sophisticated and linked system of technology. They have maintained traditions of carnival, rooted in Trinidad’s carnival with Road March, Extempo competitions, Jour’vert, and carnival costumes.

Her father (also the mayor), Antonio, discovers her mother’s fidelity and the events which unfold as a result lead to him and Tan Tan being banished to a brutal world for which they are ill-prepared. This world is populated by criminals banished from Toussaint and by the fearful characters plucked from the folklore of different Caribbean countries, douens, Moko Jumbies, and Rolling calves, to name a few. Antonio is ill-equipped to handle his fall from grace and takes his anger and unrequited thirst for power out on Tan Tan. Befriended by the douens, she flees the settlement and finds herself adjusting once more to a reality even more difficult than her original exile. She moves from village to village, taking from the rich and wicked and giving to the less fortunate, making a name for herself as the Midnight Robber as she tries to redeem herself according to the rules of the douen. “When you take one life, you must give back two.” She proves herself, as the well-known Jamaican saying quoted in the book, “little bit, but … tallawah.”

The narration of Midnight Robber adheres to the tradition of oral story-telling and merges back and forth between the telling of the story in real-time and the lore which the people of Toussaint share about Tan Tan the Midnight Robber. The descriptions are vivid and full of color and light. Readers will hear the music of the steel pan and envisage the dance of the stick fighters and the “jump-up.” The story-telling, the descriptions, and the captivating characters give the book a fairy-tale-like feel even as it deals with very serious topics of abandonment, loyalty, deceit, colonization, racism, incest, resilience, and the self-flagellation often experienced by trauma victims. Hopkinson does not spare her characters from pain, allowing them to sink to shocking, Hobbes-like depravities when they are faced with living in the most dire circumstances.

The book is written in what other reviewers have called ‘Caribbean creole’ and which the characters call ‘Anglopatwa.’ Those of us from the Caribbean may argue there really isn’t any such thing as Caribbean creole. It is decidedly Jamaican, but peppered with a few phrases popular on other islands. I found this vaguely unsettling since the carnival culture was decidedly Trinidadian. That aside, the language is delightful, especially since the Anglopatwa is not confined to character dialog but is in the narrative as well. Occasionally this is off-putting and readers may think there are grammatical errors, but the use of creole throughout the book is a necessary step to authentic Caribbean books entering the center stage of world literature.