In Roger Sale’s “Fairy Tales and After: From Snow White to E. B. White,” Sale discusses one difference between two groups of authors, namely pre-eighteenth-century writers of the fables we now read as fairy tales, and those authors who wrote after childhood became a firmly entrenched concept.

Sale points out how Madame Le Prince de Beaumont’s eighteenth century version of “Beauty and the Beast” was written in a time when authors “[knew] their audience very well, but never alter[ed] anything in the tale to suit or please their audiences; their respect for their materials [was] too great.” Sale then compares this with nineteenth century Hans Christian Anderson who, so focused on the idea of the child, opened his stories with condescending lines like:

The Emperor of China is a Chinese, as of course you know, and the people he has about him are Chinese too.

[“The Nightingale”]

It feels somehow that we have come full circle. Children and young adults recognize when authors are patronizing them and they don’t like it. This problem goes beyond books which over-explain the obvious as in the Andersen example. The dumbing-down of children’s literature, especially Caribbean children’s literature, extends to the subject matter authors choose to write about. You may be surprised to learn that, according to the Americal Library Association, five of Judy Blume’s books are on the list of The 100 Most Frequently Challenged Books of 1990 to 1999. Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland has been repeatedly challenged for promotion of drug use. The Harry Potter series has been challenged frequently for portraying black magic, Most of these challenges come from the gatekeepers-parents, teachers, and librarians who have little faith in the human mind, and authors may feel pressured to adjust their stories so that they can get past these gate-keepers.

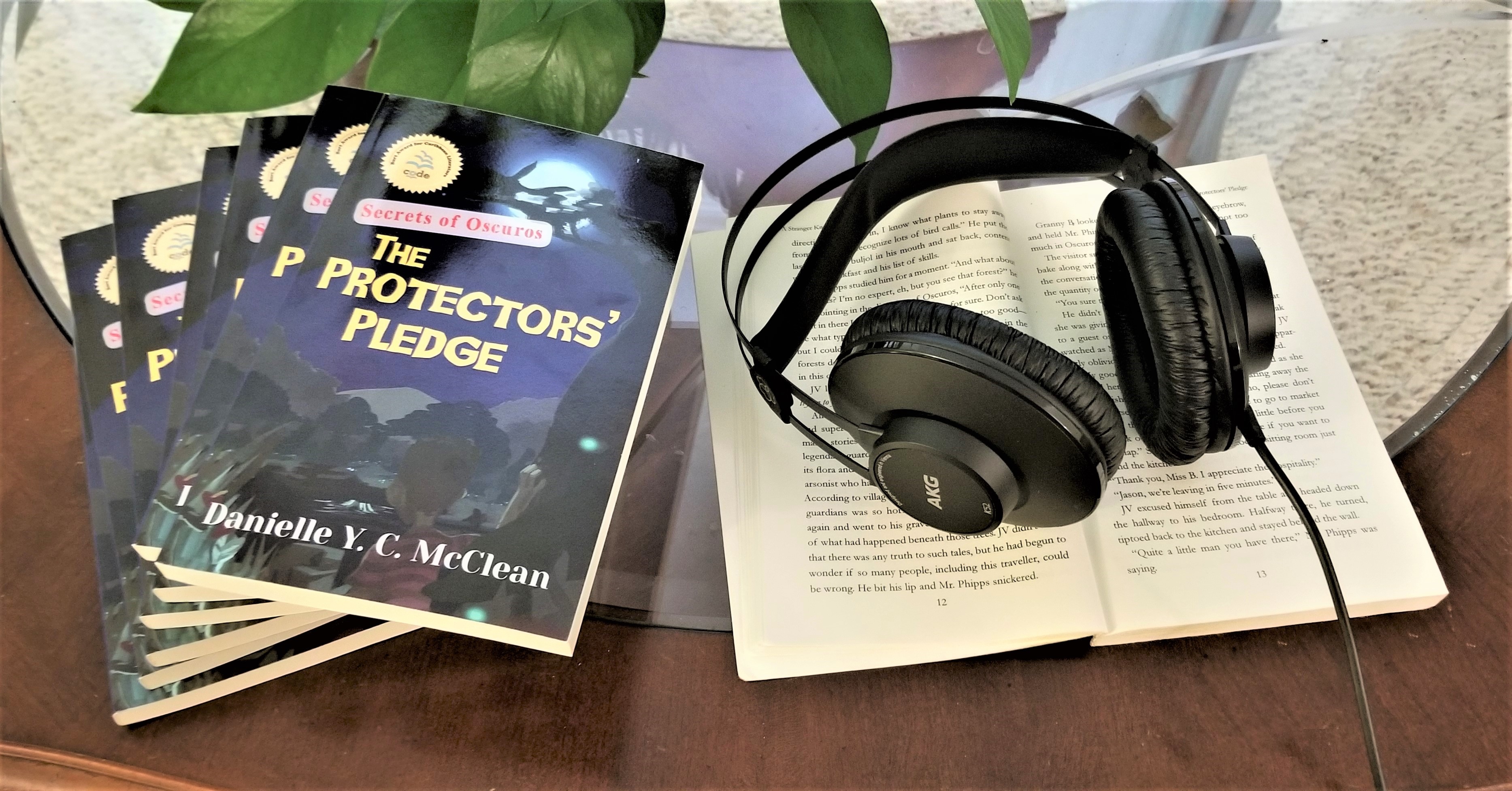

I have struggled with this in my own work. In Barberry Hill, there are many scenes in which I considered how far I could go in terms of portraying the fears the protagonist faces when his life falls apart after his brother’s death. When editing Musical Youth, we discussed the use of a single profanity before deciding to keep it because it was exactly what that particularly character would say in that particular circumstance. In The Protectors’ Pledge editors paused at the scene in which children tease Granny B. Cruel yes, but exactly what some children would do in that situation and an opportunity for those children to see what it feels like from the point-of-view of the person being teased. And then there was that penultimate page of Heidi Fagerberg’s Wilbur the Beach Pig which sends little ones into giggles but has led at least one school library not to include it on their shelves. In all of these books, we worked to stay true to the characters and the situations in which they found themselves.

Authors should not shy away from difficult topics if they reflect the reality that young people face. In the eighteenth century, women’s lives often ended in childbirth and when they did not, their value was tied up in their beauty. So mothers and step-mothers went to great lengths to retain their youth and their positions in the family structure; fathers gave away daughters who were more likely to be a strain on than a boon to the family coffers. So, the tales written then, as harsh as they may seem now, reflected the themes that needed to be discussed at the time.

Today our young people are dealing with different issues. Life is still challenging, and the books we write cannot all shy away from this. Books must include stories in which young people are generous, kind, bullied, discriminated against, raped, rescued, gay, straight, afraid, brave, heroic, cowardly, and more. Books should show people in situations where they bully others, drink, get embarrassed, have sex, abstain, try new things, and back away from challenges. Book characters should succeed often and fail often. Young people are demanding work which shows respect for them as intelligent readers who will not necessarily be led astray by a character who makes questionable choices, because don’t we all? Authors who don’t compromise their stories in an effort to coddle to their audience are likely to have the most success in the world of modern children’s books.

As I write this, I think of Force Ripe by Grenadian author, Cindy McKenzie which is an honest semi-autobiographical novel about a girl whose innocence was stolen at an early age. I also am reminded of Zetta Elliott’s novel A Wish After Midnight which takes an unflinching look at life in the Civil War era in Brooklyn. In both of these books the protagonists encounter experiences which you would not want your children to ever have to encounter, but the lesson is in the struggle and the triumph and in finding strength where you did not know it existed.

[Note: The suggestion that childhood was “invented” might seem odd to most. Up to the late seventeenth century, (historians feel free to correct me) childhood as we see it, extending to age eighteen, did not exist. After the age of seven or eight, people were treated as small adults expected to work and often to marry.]