I have to thank Ann Marie Harvey, Librarian at the Enoch Pratt Free Library, for bringing this book to the top of my reading list on which it has been languishing since it was first published last year. Ann Marie invited me to a virtual book club meeting which I would not have been able to attend if it had been held in person (#covidsilverlining) and Frying Plantain was the book being discussed. I was unable to read it before the meeting, but it sparked such an interesting discussion that I decided to read it afterwards, and I am glad I did.

I have to thank Ann Marie Harvey, Librarian at the Enoch Pratt Free Library, for bringing this book to the top of my reading list on which it has been languishing since it was first published last year. Ann Marie invited me to a virtual book club meeting which I would not have been able to attend if it had been held in person (#covidsilverlining) and Frying Plantain was the book being discussed. I was unable to read it before the meeting, but it sparked such an interesting discussion that I decided to read it afterwards, and I am glad I did.

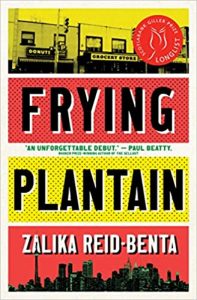

This is a book of closely-linked short stories about Kara, a young woman coming-of-age in a predominantly Caribbean neighborhood in Canada. Kara was born in Canada to a Jamaican mother. She finds herself trying to fit in by proving her Jamaicanness to the friends in her neighborhood and simultaneously to stand out by emphasizing her Jamaicanness to her Canadian friends in school. Eventually, she is able to separate from her mother and discover that she can become a new entity that is both Canadian and Jamaican.

The stories in Frying Plantain are told with a clear, unflinching voice. Kara’s most embarrassing elementary, tween, and teen interactions are laid bare, from moments of humiliation from her neighborhood friends to moments of fear in conflicts with her mother. Reid-Benta does a good job demonstrating that delicate balance of love and toughness indicative of the parental approach of a certain generation of Caribbean-Americans. While we may cringe at the some elements of the relationship between Kara and her mother, we never doubt that it is built on love.

In the midst of this search for her cultural identity, Kara also seems to be on a search for her sexual identity. She longs to feel the stirrings that her friends describe and the desperate passion she hears coming from the couple in the apartment next door, but she is unable to experience this herself. She protects the secrets of her philandering grandfather and, when she finally has a boyfriend, she is so emotionally distant from him she never even reveals his name. Instead, she refers to him as “the boyfriend” giving the impression that the relationship is more of a laboratory experiment instead of love. Whether this inability to connect is a reflection of the failed relationships she sees around her or something more fundamental, the reader is left to decide.

The stories touch sharply on multi-generational pain, the legacy of abuse, and the way that women’s lives are impacted by the men they love. The inability of Caribbean parents to communicate with their children, and often with each other, is also a powerful theme. The book is, I believe, targeted at young adults, however, it focuses quite a bit on the issues of the generation that moved north in the 1970s. I question whether young people of Caribbean descent today will see themselves in this story.

All-in-all, an enjoyable read.