|

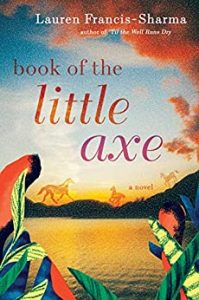

When I heard the premise of this book, I was intrigued and skeptical. A woman of African descent from Trinidad ends up in what is now known as Big Horn, Montana in 1830? Really? The likelihood and the logistics baffled me. Well, Francis-Sharma handles this masterfully with confidence backed up by compelling characters, complicated relationships, and what must have been a tremendous amount of research. |

The storytelling begins in 1830. Victor and his parents have been absorbed into the Apsáalooke people despite not having been born into the Crow nation. When a tragic accident brings Victor into conflict with his adopted people, his mother, Rosa, takes him on a journey in which he discovers the truth of his origins and hers.

Book of Little Axe is written in three well-researched threads. Loosely entwined at first, the weave of the story lines becomes increasingly tighter until they fuse into a single spell-binding narrative. We begin with Victor who is struggling on many fronts. He seems to be perpetually on the outer bands of his friend group, unable to achieve his vision, unable to hunt as well as they do, unable to fit in with the effortlessness of his best friend, Like-Wind. It is easy to connect with Victor, as, even though he believes he has “done everything wrong,” he is determined to continue trying and to succeed.

Then we are transported to Trinidad in 1796 where we meet the Rendóns, Victor’s grandparents, Rosa’s parents. This switch took me out of the story as I tried to orient myself into the idea of black people in 1796 in Trinidad owning land and businesses, but this was indeed possible under Spanish rule, just before the British arrived. The Rendóns lived a relatively comfortable life, but Francis-Sharma chronicles a slow slippery decline as the political landscape changes and allegiances fall apart. Rosa’s father, Demas, faces some impossible choices while trying to protect his family. In the midst of this all, Rosa is a spirited young woman, more interested in farming and animal husbandry than household management, the latter being what is expected of someone endowed with a female body, a gift she considers a curse.

The third thread is the story of Creadon Rampley, a wanderer of unclear ancestry trying to make a life for himself in the cruel environment of the American West around 1800. Francis-Sharma inhabits Rampley’s head, or perhaps it is the other way around, so entirely that I forgot that I was reading her words and not listening to Rampley’s own account of his life.

Francis-Sharma glosses over the mechanics of Rosa’s journey from Trinidad to the United States, which is fine since the important journeys that Rosa and Victor makes are chronicled in beautiful detail. I thought that the ending was a bit rushed. I had to re-read to understand exactly what transpired, however this is minor. While Victor’s journey of discovery ends tragically, Francis-Sharma manages to leave readers with lots of hope for the future of the people whose lives we lived in the course of the book and for the rugged Western landscape that she portrays so effortlessly.